This article appeared in the Winter 2007 issue of Texoma Living!.

The oystermen who worked the estuary of Maryland’s Lynnhaven River kept a special barrel for the largest, choicest specimens they raked up from the waters of Chesapeake Bay. “For Mr. Brady,” read the label on the barrel, and when the catch was in, the oysters were iced down and loaded onto an express train bound for Manhattan and Charles Rector’s restaurant. James Buchanan Brady, “Diamond Jim,” liked to start an evening of gustatory excess at his favorite restaurant with two or three-dozen Lynnhavens on the half shell before moving on to the ducks and chops and steaks and lobsters to come.

Brady was a teetotaler. His beverages of choice were orange juice and lemonade, but in that he stood apart from most of the other customers who crowded Rector’s, Delmonico’s and Sherry’s each evening. They preferred Champagne. Representatives from the two biggest Champagne importers, Mumm’s and White Star, made the rounds each night, sending magnums of their wine, with a card and compliments, to patrons whose cachet would add sparkle to the brand.

The time Mark Twain dubbed “The Gilded Age” could just as well have been called the Age of Oysters and Champagne, and why not? Could anything better symbolize the good life?

There are five edible species of oysters in America, although only three of these are considered to be of a quality to be served on the half shell. The Ostrea Edulis is a European immigrant, successfully cultivated in Maine and the Pacific Northwest. Called Dorsets or Whitstables in England and Belons in France, they are symmetrical in shape, round, and eminently edible. They should never be cooked.

The Olympia oyster, from Puget Sound in the state of Washington, is the only known type of Ostrea Lurida. Olympias are small, most about the size of a quarter, but their flavor is robust with a strong redolence of the sea.

The most common species of oyster in America is the Crassostrea Virginica. Ranging from Prince Edward Island to the Gulf of Mexico, these oysters take on subtle differences in taste depending on where they live.

The best known of these Atlantic or Eastern oysters are the Malpeque from Canada, the Cotuit from Nantucket, Wellfleets from the spring-fed salt marshes of Cape Cod, Bluepoints and Box Oysters from Long Island and the Chincoteague, Kent Island, and Patuxents from the waters of Chesapeake Bay off Virginia and Maryland.

Jim Brady’s Lynnhavens are gone, but perhaps not for long. In 2007, Maryland and Virginia built new oyster reefs and will soon introduce baby oysters, called spat, back to the Lynnhaven River.

The best known oysters of the Gulf of Mexico are Florida’s Apalachicolas, with green tinged shells and a coppery flavor, and Breton Sounds from the Mississippi delta. When Antoine Alciatore created Oysters Rockefeller, he probably used Apalachicolas.

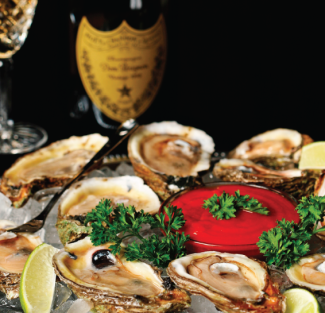

For some oyster lovers, adding anything to the bivalve is sacrilege. Those less pure might consider a hint of lemon, a dab of Sauce Mignonette, a grind of black pepper, or a drop of hot sauce. A New Orleans favorite calls for a touch of Pernod and a bit of caviar.

In Ireland, oysters call for a glass of stout or better still, the half stout, half Champagne mix known as black velvet. Most any dry white wine will complement the complex flavor of the oyster, but first on the list is, of course, Champagne.

There are four basic considerations in choosing a bottle of Champagne: Marque, Style, Vintage, and Dryness.

Marque

Marque is simply the brand. French Champagne comes from the region of the country ninety miles northeast of Paris near the Belgian border. Unlike other wines, Champagne is known by the name of its maker, rather than the name of a vineyard. Champagne comes from one of three areas within the region, Reims, Marne or Côte des Blancs. Among the better-known Champagne labels are Bollinger, Piper- Heidsieck, Krug, Möet & Chandon, Taittinger, and Veuve Clicquot-Ponsardin.

Style

Pink Champagne is increasing in popularity. Champagne rosé is made by adding a bit of red wine to white before bottling, although better examples are made entirely from the Pinot Noir grape. Applying the Champagne method to a rosé may also produce pink Champagne.

Blanc de Blancs, made with the Chardonnay grape exclusively, is a lighter and more delicate wine. It is also more expensive than blended Champagnes.

Blanc de Noirs is relatively rare and usually costly. Made from Pinot Noir or Pinot Meunier this Champagne is golden and fullbodied. It holds its own well with food.

Vintage

Nonvintage Champagne, which accounts for eighty-five percent of the market, is blended from grapes grown over several years. Vintage Champagne come from a single year’s harvest and cannot be sold for at least three years. The best of the vintage Champagnes needs at least a decade to mature.

Several companies now offer a De Luxe designation. This is reserved for vintage wines from exceptional years which bring exceptional prices.

Dryness

Champagnes are rated by their residual sugar content. From the driest, they are: Extra Brut (no sugar added), Brut (dry), Extra Sec (off-dry to medium dry), Sec (medium-dry), Demi-sec (sweet), Doux (very sweet and rich).

Most Champagne is Brut or Extra Sec.