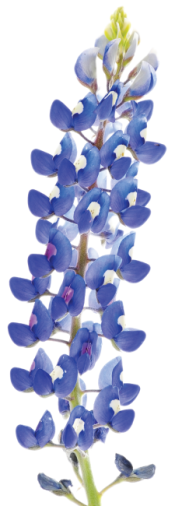

Do you think bluebonnets are what Texas wildflowers are all about? Actually, in Texomaland, most of those legendary spring beauties come to our roadsides only as a courtesy of government agencies that sow, mow, and otherwise outwit nature into producing them. Same for the gorgeous red clover that lines parts of US 75 every spring. Some folks think that once the bluebonnets go to seed and the clover turns manila brown, the wildflower season is over, but if you want to be bowled over by real native flowers, get ready—the best is yet to come.

Do you think bluebonnets are what Texas wildflowers are all about? Actually, in Texomaland, most of those legendary spring beauties come to our roadsides only as a courtesy of government agencies that sow, mow, and otherwise outwit nature into producing them. Same for the gorgeous red clover that lines parts of US 75 every spring. Some folks think that once the bluebonnets go to seed and the clover turns manila brown, the wildflower season is over, but if you want to be bowled over by real native flowers, get ready—the best is yet to come.

Roadside flowers are the glory of Texomaland throughout the whole warm season. Some of the most handsome are so common that we think of them as weeds or don’t notice them at all. But if you watch closely as summer winds down and fall tunes up for the year’s last performance, you may witness some of the most beautiful native flowers of all.

False purple thistle (Eryngo leavenworthii)

It boasts the most striking purple of any Texas wildflower. It may not be a true thistle, but if you inspect it, you’ll see immediately why it’s called one. Look, don’t touch. Ernygo thrives in thin or hard soil over white rock, so you’ll find it in high spots along country lanes.

Camphor weed (Pluchea camphorata)

This lovely flower with the ugly name can be found growing in marshy areas, as well as in ditches where mowers never venture. Last fall, it bloomed profusely along Airport Road inside the North Texas Regional Airport (Perrin Field). Backed by goldenrod, it painted a spectacular picture for several weeks. Look for it again this year.

Snow on the prairie (Euphorbia bicolor)

Common along fence rows and in neglected pastures, this brightly-colored plant is everywhere. In fact, it’s so familiar that it’s easy to overlook. A closer glance reveals it showing off with foliage, rather than flowers, just like its relative, the poinsettia.

Goldenrod (Solidago altissima)

Don’t be misled by the myth that goldenrod causes hay fever. It got that rep because it blooms at the same time as the real villain, ragweed, and steals all the attention with its thick golden tresses. Cut down the ragweed, not the goldenrod. Look for it along country roads all over the area.

Gayfeather (Liatris elegans)

This flower is not named “elegans” for nothing. Where you see one resplendent head glowing in the autumn sun, there will often be many, almost always on a sloping roadway or hillside. They really do look like feathers elegant enough to grace a lady’s hat.

Maximilian sunflower (Helianthus maximiliani)

The sunflowers often yearn to reach the sky, and this big fellow is one of the most ambitious, stretching up to ten feet in good conditions and spreading widely along grasslands and ditches. Its seeds are an important food source for native birds and deer.

Browneyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

Seen as often in home and business landscapes as in the wild, this lovely yellow daisy blooms its head off from spring through fall, lending color to the driest and hottest times of the year. It thrives in fields, where it can spread rapidly to create meadows of golden blooms.

Lemon beebalm or Prairie horsemint (Monarda citriodora)

Rub a leaf of one of these beauties and you’ll learn where its lemony-minty names come from. Flower color ranges from the palest pink to almost purple, and the whole plant is aromatic. This native herb has a long history of medicinal use by Native Americans and others.

Texas lantana (Lantana horrida)

Lantana is another way of saying “tough.” It grows almost anywhere, in sun or shade, but does favor quiet country roadsides. If you stumble across one of these five-foot shrubs bearing bright orange and yellow and red flowers, you won’t mistake it for anything else. Butterflies love it.

Common sunflower (Helianthus annuus)

Sunflowers, which will grow almost anywhere, would be more widely appreciated if they didn’t arm themselves so well. Their stems bristle with tiny spines which, if they brush across bare skin, can cause an itching rash to make a grown man cry. Cheery giants of the wildflower world, they often reach ten feet in height. One reason for their vigor may be that Native Americans selected, cultivated and improved them for thousands of years, as an important source of food, fiber, and medicines.

Jessie Gunn Stephens is a Master Gardener and has written several books including Touring Texas Gardens. Read a review of this book at www.texomaliving.com. She writes a regular gardening column in the Herald Democrat.

Photos by Jessie Gunn Stephens