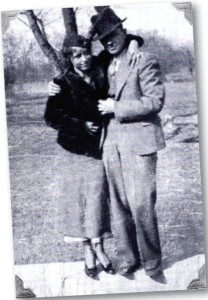

The saga of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow is the substance of which legends are made—and great Hollywood movies too. Who can forget the 1967 motion picture classic that starred Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty as Bonnie and Clyde?

“We rob banks,” will rank as one of the greatest movie lines ever. That film received eight Academy Award nominations and two Oscars. Could a new Bonnie and Clyde movie possibly surpass that masterpiece? America and the world will get the chance to decide later this year. A new first-run version, The Story of Bonnie and Clyde, is currently in production. It is scheduled for release during the fall of 2010. Kevin Zegers and Hillary Duff will reprise the roles played by Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway.

The new movie will have something that was completely left out of the plotline in the 1967 film, namely, the real life role played by Lee Simmons of Sherman, Texas, in the hunt for Bonnie and Clyde. Actor Lee Majors of bionic man fame will portray Simmons, who served as director of the Texas Prison System in the early 1930s, during the years Bonnie and Clyde were robbing banks in Texas and the Middle West. It was prison director Simmons who declared the two outlaws had to be stopped at any cost. He oversaw their demise by setting Captain Frank Hamer and a group of lawmen on their trail.

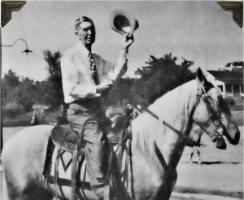

The career of Sherman’s Lee Simmons proved just as colorful as those of Bonnie and Clyde. He was every bit as tough and hard-bitten as the Barrow gang, although scrupulously honest and above reproach. Born in the East Texas hamlet of Linden in 1873, Simmons moved with his family to Grayson County while he was a child. Growing up near Sherman, he attended Austin College for two years before he transferred to the University of Texas. His brother D. J. Simmons was a prominent Sherman attorney and a member of the State Legislature. The younger Simmons hoped to follow in his brother’s footsteps by becoming a lawyer too.

Those plans came to an unexpected end at age twenty-one when authorities arrested him. Protecting himself, Simmons had gotten into an old-fashioned shoot-out with blazing pistols against a man who had been disparaging his family, most likely for political reasons. He shot dead his adversary. Simmons went on trial for murder. A jury quickly found him innocent by reason of self defense, but this experience caused Simmons to turn away from practicing law as a potential career.

Instead, Simmons turned to cattle raising and mule trading. This proved to be a very lucrative business for him. His honesty and forthrightness as a livestock trader remained beyond reproach. In the fall of 1912 a group of citizens urged Simmons to run for sheriff of Grayson County. The county had “skiddy row” districts where bootlegging, illegal gambling, saloon rowdiness, and worse proved the order of the day. Unsubstantiated rumors alleged the incumbent sheriff was in cahoots with the bootleggers and gamblers. The time had come, local citizens told Simmons, to clean things up.

Simmons agreed and campaigned on a reform platform. He won handily. Two days after the election, he was resting at his Sherman home when a man called him outside to the street because a woman wished to talk with him. Ever gallant, he walked to a waiting car, where she asked, “Are you Lee Simmons?” to which he replied, “Yes Ma’am.” She drew a revolver and fired five shots at point blank range, almost killing him on the spot. Investigation later determined she and her male accomplice were friends of the recently defeated sheriff.

Simmons survived his wounds. Several weeks later, he took the oath of office while still bedridden. Sheriff Simmons cleaned up Grayson County in a spectacular series of raids, successfully banishing the bootleggers and the gamblers. He sometimes returned to his office desk with the barrel of his revolver still warm. His work done after two terms, Simmons resumed his private life and spent the 1920s as a Sherman businessman. Lawmen across the state, however, regularly sought his advice and counsel. Simmons also served as a member of the Texas Prison Commission and advised a series of Texas governors on law enforcement policy.

In 1930, the Governor of Texas appointed Simmons as General Manager to direct the State Prison System. Simmons went to Huntsville, where he speedily took charge, overseeing a sweeping reform of the state’s penitentiary system. He established the annual Texas Prison Rodeo, expanded farming operations to have the prisoners produce their own food, and instituted a series of changes that improved living conditions for inmates. Historians today consider him one of the founders of the modern prison system.

Clyde Barrow was an inmate during Simmons’ time as director, but the two never met. The outlaw from Dallas served his term and was released. “He was just a convict number to me,” Lee once recalled of Barrow, “one of the anonymous men assigned to the Eastham Farm.”

After being released, however, Barrow lost his anonymity with a January 16, 1934 prison break that made national news. An inmate work gang had marched outside the Eastham unit that morning to cut timber under the supervision of armed guards. The detail included several members of the Barrow gang who, unknown to prison officials, had hatched a bold escape plan. Barrow and Bonnie Parker waited nearby under the cover of brush with a fast car at hand. Barrow opened fire on the guards with a machine gun, killing one of them. In the ensuing mayhem, the inmates from his gang jumped into the car, and Barrow sped them away to freedom.

Lee Simmons vowed to avenge the guard murdered in the escape and stop the Barrow gang at any cost. He went to Austin where he met with Governor Miriam A. Ferguson. Simmons explained to her that extraordinary measures had to be taken right away in order to bring the Barrow gang to justice. He told Governor Ferguson that he was the very person to do it. She gave him the special powers he requested for this purpose. Simmons would head a task force charged with stopping Bonnie and Clyde. He speedily picked Captain Frank Hamer from the prison staff to head a posse of experienced lawmen, and the hunt began within days. Simmons would supervise their activities from his office. “No matter how long it takes,” he told Hamer and his men, “I’ll back you to the limit.”

Simmons understood that leaks to newsmen—or worse, to the Barrow gang—might jeopardize the whole effort. For that reason, he and Captain Hamer operated entirely in secret. They never met at the prison; instead Hamer gave his boss regular reports privately, in secluded hotel rooms around the state. During one of these conversations, the captain asked Simmons about bringing in Bonnie and Clyde dead or alive. Simmons replied, “The thing for you to do is put them on the spot; know you are right—and then shoot everybody in sight.”

That is exactly what happened to Parker and Barrow near Arcadia, Louisiana, on the morning of April 23, 1934. A stoolpigeon in the Barrow gang secretly gave their location away in exchange for a criminal pardon negotiated by Simmons with Governor Ferguson. Hamer and his men were concealed along the side of a country road. They opened fire as the two outlaws drove by in a stolen Ford V-8 sedan, riddling the automobile with several hundred bullets. As Simmons later noted, “Bonnie and Clyde had come to the end of the trail.” The posse gratefully presented Simmons with one of Clyde’s revolvers taken from the bloody death car.

Lee Simmons left his job as prison director the year after he successfully supervised the hunt for Bonnie and Clyde. Desiring a more sedate life with his family, he returned to Sherman, where he became clerk the United States Federal Court and later served as an administrator of the Southwestern Power Commission. He also continued his interest in cattle raising. As Dallas newspaper columnist Lyn Landrum once wrote about Simmons, he “loved cattle, loved cowmen, and loved the open country.”

Simmons was an affable man, and over his lifetime he established an ever expanding circle of friends. One of them, Sherman rancher Pete Hudgins, named his son for Lee Simmons in 1921, and the Grayson lawman counted cowboy movie star Tom Mix, humorist Will Rogers, and a host of important political leaders in Texas as his friends, as well. On his death in 1957, the Dallas Morning News told its readers that “his career spanned the era from the six-shooter to the atomic missile.”

Now Lee Simmons, in the person of actor Lee Majors, will be on the silver screen for all to see this coming fall in the new Bonnie and Clyde film, although almost certainly, the real Simmons would not have approved of the outlaws becoming the subjects of movie adulation. But no matter how Bonnie and Clyde are portrayed in the upcoming film, either sympathetically as tragic heroes or more harshly as counter cultural anti-heroes, it was in life that Sherman’s Lee Simmons had the last word on them. Writing in his memoirs about Bonnie and Clyde, he observed “as they had sowed, so also had they reaped.” To him, they were always lawless murderers, plainly and simply so.