Traveling west from Sherman on U.S. 82 where Bar 7 Road hits the highway, you top a rise. The horizon reaches out as the land falls away, and you are out of the cross timbers and onto the prairie. This dividing line is a great fold in the earth’s crust running from central Texas to Montana. Geologists call it the Preston Anticline, and it is where the West begins.

It is the beginning of the sea of grass stretching from central Texas north to the Great Plains, grass which provided the sustenance for the great herds of bison that moved between the northern and southern plains for thousands of years before man came to the land. The dominate ground cover is Buchloe dactyloides, buffalo grass, and what was good for the buffalo, was equally good for cattle.

The great brands of West Texas, symbols which conjure the iconic images of the American cowboy – XIT, 6666, Pitchfork, T Anchor – did not come to be until after the U.S. Army had wrested the Southern Plains, once and for all, from the Comanche, the Kiowa, and the Cheyenne during the Red River War of 1875-1875. But a decade before that, the focus of the Texas cattle business was Grayson County. It was the first jumping off place for the sea of Texas longhorns that flowed north, to feed a hungry nation.

In the spring of 1866, more than 250,000 cattle came up the Shawnee Trail and crossed the Red River at Rock Bluff near Preston, before striking out across the Nations toward markets in Missouri and eastern Kansas. In time the drovers would cross their herds farther west, at Red River Station and Doan’s Store to move up the Chisholm and the Western Trails, but it was here, on the edge of the Cross Timbers, where it all began.

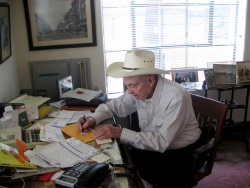

It is more than happenstance that the road atop the anticline is called Bar 7. Bar 7 is the brand of Lee Hudgins, and he and his family have been a part of the cattle business in Grayson County for five generations. On a crisp, sunny day in early autumn, he stands on the ridge, looking west into the sun and points out the changes in the topography. He has an eye for the land.

When the United States entered World War II, Hudgins left the University of Texas and applied his eye for the terrain to the making and study of maps for the U.S. Army in Europe. “I didn’t really graduate,” he says, “but they gave me a diploma anyway.” He bends over, cups a tuff of buffalo grass and talks about how it is nutritious and hearty and will thrive in the semi-arid conditions of the Great Plains, and he talks about water. “You can have too much water, as well as too little. Sherman sits right on the line where there is too much rain back to the east, and often not enough farther west,” he says. “So nature works out pretty good here.”

The cattle business is about grass and water. Both are essential to success. “You have to have reliable water,” Hudgins says. “Way back, the only place you could start a ranch was on a river. The biggest spread around here was the Goode Ranch. It bordered on Red River and ran south. A lot of the land west of 1417 was once that ranch.

“Southwest of Sherman, around Dorchester and Gunter, there sure was good native grass, but the ranches didn’t come until they put the first windmills down there. The Kimberlin Ranch put in the first windmills we’d seen around here.”

Two years ago, son, Pete Hudgins, rode a back hoe for much of the fall, digging out the stock tanks on the ranch to make them deeper. Deeper tanks collect more of the rain when it comes, and last summer, with no rain and some ranchers selling off animals they could not water, Bar 7 had no such problems. A cowman can’t think just about today, tomorrow, or next week or next month. A good cowman takes the long view, and prepares for what may come.

Hudgins has a reverence for the land, and he sees in it things others never notice. “So much of the country is cut up,” he says, “not like it used to be,” and as he drives the back roads west of Sherman, he identifies parcel after parcel of land with a hint of nostalgia in his voice. “My father owned that section, he will say, or we used to lease that pasture over there and work cattle on it.”

“My father would really be bothered by the condition that pasture’s in today,” Hudgins says as drives past a field, partially plowed and thick with weeds. “The folks who own it now don’t take very good care of it. They cut part for hay and let the weeds get out of hand. It’d take several years and a lot of work to put it back into shape. But it’s their land, so there’s nothing you can do.”

It is a fine art, managing the land, and it is as much a part of being a real cowman as sitting a horse. He knows when to graze, and when to let the land lie fallow and recover. Many of the part-time ranchers, dabblers really, do not have the knowledge or the interest to do it right. And seeing the land misused hurts men who understand it. For in the long run, it is about the cattle, and it is about the land, and it is about a way of life that the Hudgins family has been a part of for 150 years.

L. Nathan Hudgins, came to Texas from Virginia before the Civil War. He bought land in Grayson County, but in short order determined that the area was too dangerous for his family. “The Indians were so bad, he moved his family to a place east of Fort Worth, where DFW airport is now,” said Hudgins. “He made a statement, that if a man wanted to fight Indians and outlaws that was his business, but he shouldn’t subject the women and children to that.”

The ranch near Fort Worth was a successful one, and Nathan Hudgins, a devout Methodist, built a church and a school where the city of Grapevine now stands. He had four sons, three of whom died in the Civil War. The remaining son, Thomas B. Hudgins came to Grayson County after the war to run the ranch near Sherman.

“He wasn’t making a living on the ranch,” said Hudgins, “but there were a lot of settlers coming into the area after the war, so he went to work for a land development outfit out of New York City. They bought ranches and cut them up into small farms.”

The land company offered one stop shopping for the newcomers. In addition to land, they sold horses and mules and cows to get the farmers going. “Where Woods Street is in Sherman, near Houston along the creek, is where they kept the livestock. My grandfather died when I was about eight; I do remember him, but that’s about all.”

Thomas Hudgins may not have been a cowman, but his son Pete, Lee Hudgins’ father, was one of the best. “My father went to Captain LeTellier’s School on Walnut Street, and it was marvelous place. The ranchers from Texas and the Indian Territory sent their sons to school there, and it was remarkable how many of my father’s generation went to Captain LeTellier’s. That school made quite a mark on Texas because so many of the boys who went there later did so much as men.”

Pete Hudgins started buying horses when he was teenager, keeping them at the family home, where Piner School now stands. Thomas Hudgins still had connections to the land business and one of young Pete’s early jobs was delivering building supplies with a team and wagon to the farmsteads. “He learned the country pretty well, and saw what was out there,” Hudgins said. And armed with a solid knowledge of the country, Pete began buying land when parcels came up for sale.

While Pete Hudgins eventually owned some fairly large blocks, much of his land was scattered out in smaller parcels, bought from small farmers who went bust, or ranchers who could not make a go of it in a demanding and often unsettled business. Often, when he needed more room, he would lease property for his livestock. “He leased the Marshall Ranch in the northwest part of the county. It went from the Red River almost to Pottsboro, about 8,000 acres, and at one time or another leased from the Goodes and the Kimberlins, too,” said Hudgins.

Ranchers do not talk much about the size of their operations. It would seem untoward to a man like Lee Hudgins, and it is just not done. Men who try to impress others with what they have done, or what they have got, are, in the time tested Texas vernacular – “All hat and no cows.”

As Pete Hudgins built his cattle business during the 1920s and 30s, he saw to it that his two sons, Lee and Tom, earned their spurs, both literally and figuratively. When Lee came home following the war, he said he always knew he would follow his father Pete into the cattle business, but not around here. He wanted to move to Montana. But when he got out of the army, he found there was work to be done at home.

“My mother had died shortly after I got back, so there was a tremendous job gathering several thousand cattle that had to be counted and appraised for the inheritance tax,” he said. “Naturally, I couldn’t go off and leave my father with that, so I stayed and it’s best that I did.” Tom had come home, too, but he had been badly injured in the war, and was not physically able to follow the life of a cowboy. He turned to managing numbers, something his father was a whiz at, and became an accountant.

While the market for cattle had been good during the war, the communication and transportation end of the business had seen considerable disruption. But Pete Hudgins had been through the hard times of the depression and was well equipped to handle what ever came along. “A lot of the hands had been gone, but he had a cadre of real good cowboys,” said Hudgins. “Joe McDonald, Arthur Lacy, Cicero Jones and Bass Jones too, although they weren’t related, those fellows were all sure enough cowboys.”

“A real cowboy can do it all,” he said. “Most ranches wouldn’t have but few real cowboys. They’d be in charge of all the wranglers and supervise what they did.”

Despite a lifetime in the saddle, Hudgins is hesitant to call himself a cowboy. “I never was a really good roper,” he said. “I guess I could have been, but I didn’t practice enough.”

As far as Hudgins is concerned, there was no finer cowboy anywhere than Malcom Lacy. Everybody called him Mutt. “I’d only been home for a couple of days, when Mutt came up to me on the street in Sherman and said he was looking for a job.”

That was in 1946, and Mutt Lacy rode for the brand as Hudgins’ foreman for 50 years. He passed away about a year ago, but the standard that he set is still part of the Bar 7, carried on by his son, and his grandson. Lee’s younger son, another Pete Hudgins, has come back home after a few years on the northern range to take his generation’s place in the scheme of things, and now handles most of the day to day running of the business and the ranch.

It was the younger generation unloading cattle at the pens at the old Meadowlark Dairy west of Sherman one morning not so long ago. “These calves are pretty wild,” says one of the cowboys. “Better stay out of the pen.” The cattle are pushing and shoving in the tight confines, and in the middle of it all is not a safe place to be. Lee Hudgins knows that and watches from the side. Being a cowboy can be dangerous work, and Hudgins knows that, too. At 86, he has more than done his share of time in the pens.

“Last year, we had a horse die while a cowboy was riding him. Just fell over dead, trapped the cowboy underneath, but we got him out all right.” He watches the cowboys work for a while. “They haven’t been worked very well,” he says, referring to the new batch of calves. “That’s why they’re kind of wild.”

Good cowboys are quiet cowboys, at least most of the time. They handle the stock with a minimum of noise and hurrah, and they are easy on the horses, too. It is not at all like the movies or the rodeo or the Wild West show. Hudgins allows that real cowboys are raised to the job, and they are getting harder to find.

Raising beef cattle is a value added business. Hudgins takes calves, some born of his own cows, many more bought from other ranches and works them to start them on the way to become Big Macs and thick steaks. When they are ready, he sells them to someone else who will full feed them— finish the process with corn and grain—and sell them to the meat packers. That explanation is exaggerated in its simplicity and does little to describe the far more complex workings of the cattle business, but it gets the idea across.

One of the biggest changes in the business over the years is the size of the outfits. The days of the giant spreads like the King Ranch or the 6666 or the Pitchfork are dwindling. Instead of thousands of cattle, small operators deal in hundreds or even less. This tends to keep the beef market down, as small producers, for whom the income from cattle is not their principal livelihood, sell whenever they need some cash, rather than holding the animals back for better prices.

“Most of our cattle now go to Nebraska. That’s the best place for real fancy Hereford and Hereford-Angus cross feeders. They pay a premium for premium cattle, but they’ve got to be premium. They used to go to Iowa and Illinois, but now it’s Nebraska,” Hudgins said.

Hereford and Angus are the breeds on the Bar 7. They produce the best beef, and Hudgins carefully breeds his own stock to maximize the best qualities of each. You can see it in the cattle. They are big, strong looking, with deep color in their shiny coats. Even one who knows little-to-nothing about livestock can see the quality in these animals.

Pete Hudgins died at 93, a cowman to the end and part of a culture that seems almost anachronistic in a time when the misrepresentations and misdeeds of the modern business world are daily fodder for the front page. But the idea of doing business on trust and a handshake lives on with Lee Hudgins and other cowmen like him.

After more than half a century, Hudgins knows the people he sells to and buys from. It is a tightly woven fabric of connections and associations that go back for generations of cow people. And it is done on trust. “I’ve sold cattle to people and months later when it turned out they brought more money than expected, the buyer would send me another check. I’ve done the same thing.”

Times change. The cattle pens along Post Oak Creek are long since gone. The railroad sidings at Pottsboro, where the Katy shoved long lines of empty stock cars waiting to be loaded, are gone, or gone to rust. Certainly the cattle business has changed, nothing stands still, but some aspects stay the same. A cowman keeps his word, looks after his animals, deals with the myriad of problems, some big, some small, that keep ranches going from day to day. Hudgins is still a part of that process.

There is truth in the rhyme “Some states were made and some were born / But Texas grew from hide and horn.” The destiny of the Lone Star rode in the saddles with thousands of cowboys and on the backs of millions cattle. What ever changes, Texas will always be beholding to families like the Hudgins who have been part of that destiny for five generations. And to individuals like Lee Hudgins. He’s a cowman.

This article appeared in the Winter 2006 issue of Texoma Living!.