This article appeared in the Winter 2008 issue of Texoma Living!.

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of regular articles based on present and future exhibits at Sherman’s Red River Historical Museum.

Assimilation of the Southern Plain’s Native Americans into the White Man’s Society

The number of exhibits that have been brought to the Red River Historical Museum in Sherman is impressive, and so is their quality. The museum’s success rises from a long process of development by the volunteer citizen board of directors, under the leadership of museum director, Marcia Rolbiecki.

Most of the programs at the museum are funded by contributions from the Friends of the Red River Historical Museum and grants from the Sherman Council for the Arts & Humanities. Located ind owntown Sherman, the museum attracts visitors from across Texoma and the nation.

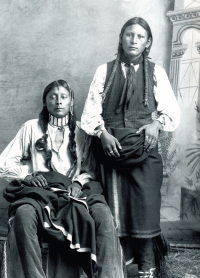

“In Citizen’s Garb: Images of Native Americans on the Southern Plains, 1889-1891” will be installed at the museum through January 19, 2009. The exhibition consists of fifty-three photographs, modern re-strikes made from original glass negatives, taken between 1889 and 1891 by the team of William J. Lenny and William L. Sawyers.

During the late 19th century, after tribes were forced onto reservations in Oklahoma and Indian Territories, they were required to adopt Euro-American culture. The exhibition explores how dress, and life, changed for the Kiowa and Comanche tribes, as they adapted to the transition from their past to a radically different future.

Following the annexation of Texas in 1845 and the end of the Mexican War in 1848, United States Indian Policy on the Southern Plains focused on ending Indian raids across the Red River into Texas and even into Mexico and negotiating the right of transit for overland trails such as the Santa Fe Trail.

At the conclusion of the Civil War, the government embarked on a new Indian policy, known as the “Small Reservation Policy.” This policy was based on the assumption that Plains Indians could no longer sustain a buffalo-hunting culture, since the buffalo herds had been greatly depleted and would soon be exterminated.

Indian policy was directed toward the assimilation of Native Americans into Anglo-European culture, including language and religion, by transforming buffalo hunters into farmers and by gradually reducing the size of tribal land holdings through individual allotment, opening “surplus” tribal lands for non-Indian homesteads.

The Small Reservation policy was initiated on the Southern Plains by the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek, negotiated with the Kiowas, Comanches and other Southern Plains tribes in 1867. In placing their marks on the treaty document, Comanche and Kiowa chiefs gave up tribal claims to lands in Texas—including the entire Texas Panhandle—and were to be confined to the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Reservation—3.7 million acres in southwestern Oklahoma.

Fort Sill was established in the center of the reservation to ensure compliance to treaty provisions through military force. A new generation of tribal members would grow up as reservation dwellers.

The changes in the Indians’ circumstances were profound. Following the Civil War, white buffalo hunters slaughtered millions of buffalo for their hides. By the late 1870s, buffalo herds had been virtually exterminated. Within the confines of the reservation, even deer and other game soon became scarce. The summer of 1879, the Kiowas were reduced to killing and eating their ponies. So the tribes were dependent on the government for virtually everything they needed for survival.

Families would travel with their belongings to the ration-issue stations and camp there for several days. Rations included beef, bacon, beans, flour, coffee, sugar, soda, soap, and tobacco. Indian culture has little use for some of these items. Bacon and flour would be thrown away or sold for a nominal price.

These rations were managed by politically- appointed Indian Agents. Over the decade 1885-1895, there were nine successive agents. It was a virtual revolving door of men of varying abilities and levels of honesty.

The Indian Agent was also responsible to effect the social changes dictated by the governmental policy. The 19th century government policy that Indians must assimilate into white society meant that schools and churches were often agencies of change. There was little room for compromise.

The treaty guaranteed that Indians on the reservation would be supplied with food and provisions, which were to be distributed on a monthly or semi-monthly basis. “Annuity Goods” continued to be issued for a thirty-year period, ending in 1898. The treaty stipulated an annual distribution of $25,000 in goods during this period. Annuities included blankets, cloth, hosiery, suits for men and boys, needles, beads, tin cups, butcher knives, kettles, axes, and farming implements.

The distribution of annuity goods was an occasion for great festivity. The Indians would camp around the agency grounds for several days before the distribution, passing time in gambling, horse racing, game playing, dancing and singing.

The Red River Historical Museum’s exhibit, “In Citizen’s Garb,” is made up of portraits taken by Lenny and Sawyers, most of which may have been taken during the annual annuity issue.

Red River Historical Museum is located at 301 South Walnut Street, Sherman, Texas 75090 at the corner of Jones and Walnut Streets. Operating hours are Tuesday-Saturday, 10am-4pm. Suggested donation at the door is Adults $2, Children Under 12 $1.