The knock on the door of Richard Pressley’s house in Sherman on January 4, 1960, was one he never expected. Standing on the porch was Grayson County Sheriff Woody Blanton, and he was there to end the fifteen years of freedom enjoyed by Pressley following his escape from prison in 1945. Though unidentified, Pressley was the minnow salesman who was one of the subjects in the January-February Texoma Living! story (Chasing Bootleggers in Texoma) about bootleggers in 1950s. His daughter, who still lives in Sherman, read the story, admitted it was true, but added that her father was “more than just a bootlegger.” Her words and some newspaper clippings she provided compelled us to tell his incredible story.

Edgar Marion Thompson was born in 1920. He grew up hard in hard times in a two-room shanty set among the pines and red clay of Georgia. The children of the family- there were seven of them – went to work as soon as they were old enough, and education was a luxury they could not afford. Thompson quit school after the fourth grade and set out to earn his keep, but he was rebellious and impatient and wanted the money to come quickly and easily. When he and his father quarreled, the boy found a gun and shot the older man in the foot. His first arrest, for some minor offense, came when he was eleven-years-old. He was reprimanded and released, the charges dropped.

Edgar Marion Thompson was born in 1920. He grew up hard in hard times in a two-room shanty set among the pines and red clay of Georgia. The children of the family- there were seven of them – went to work as soon as they were old enough, and education was a luxury they could not afford. Thompson quit school after the fourth grade and set out to earn his keep, but he was rebellious and impatient and wanted the money to come quickly and easily. When he and his father quarreled, the boy found a gun and shot the older man in the foot. His first arrest, for some minor offense, came when he was eleven-years-old. He was reprimanded and released, the charges dropped.

At fourteen, Thompson ran into the less forgiving side of the law. Convicted of stealing a wallet from one man and a ring from another, he was packed off to the Georgia State Penitentiary at Reidsville. The facility was relatively modern, having been opened in 1937, partially as a result of shocking publicity produced by the 1932 book I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang, by Robert Elliot Burns and subsequent movie starring Paul Muni. Reidsville may have been new, but links to the darker days of penology still existed.

Thompson entered prison and started working on a work gang in 1944. About a year later, when a fellow convict stole Thompson’s watch, the fifteen year-old boy beat the man so savagely with a soft drink bottle that he was hospitalized. The next morning, a guard told Thompson that when he finished his day’s work, he was going in to solitary on bread and water for fifteen days. On that day, August 15, 1945, Thompson decided that he would not come back. One way or the other, he would escape.

The Unplanned Escape

There were two guards with the fifteen prisoners on the work crew. Thompson worked his way close to one guard and suddenly grabbed his shotgun. Another convict overpowered the second guard, disarmed him and then killed him. All fifteen prisoners fled, but most were recaptured quickly. Thompson ran with the killer of the guard, who was serving two life sentences for murder, and a third convict who, strangely enough, had only twenty days left to serve.

It had been raining for several days, and the water courses were running high. When the trio tried to ford a deep, swift river, Thompson and the killer made it across safely, but the twenty-day short timer floundered and drowned despite Thompson’s attempt to save him. The two remaining escapees decided that if they stayed in one place, their scents lost in the rain-soaked ground, the bloodhounds would never find them, so they did not move for three days. They had no food. Once when the bloodhounds got close, Thompson immersed himself in the river and breathed through a hollow reed. All the time they were hiding, they could hear an occasional gunshot as the other prisoners were being hunted down.

When they thought it safe,Thompson and his companion slogged through swamps until they found a road and two soldiers in a car. The other escapee quickly killed one soldier and would have murdered the other had Thompson not wrestled the killer’s gun from his hand. When the killer was caught, he testified at his trial that “just in case anyone ever hears of Thompson again, Thompson saved the second soldier’s life.”

Thompson split from his homicidal partner, took to the swamps again, and was soon covered with leeches and infected cuts. He stuck to trails and back roads while walking and hitch-hiking his way west. A day’s work, here and there, gave him enough money to buy food. Fearing he would be caught on the bridge, when he got to the Mississippi River, he swam across.

Richard Pressley is Born

In Louisiana, he hooked up with a traveling carnival doing odd jobs. When one of the other carnies left the show, the man on the run took his name, and Edgar Marion Thompson became Richard Pressley, the name he would carry from that time on.

Pressley left the carnival when it went into cold weather quarters in Texas during the winter of 1945-46. He ended up in Sherman, where he got a job on a farm, rising at 4 a.m. and working until dark. After the farm, he worked for a landscaper, an ice company, and a construction outfit. For more than five years, Pressley worked hard in and around Sherman, always keeping a low profile, but the long hours and low pay brought those old longings for the “quick dollar and dangerous life.”

When the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the sale of alcohol nationwide, was repealed by the ratification of the 21st Amendment in December 1933, the “wet” vs. “dry” question became one for state regulation. Texas devolved the matter even further, allowing local governments at various levels to pass on the question. Grayson County stayed dry, so the closest place to legally purchase alcohol without restrictions was Dallas.

This led to a lucrative business opportunity for men willing to run whiskey, legal and illegal, from Dallas to Grayson County. Like industrious entrepreneurs throughout history, they identified a need, and sought to fill it, for good cash premium of course. For a man like Richard Pressley, with a yen for a little danger and disregard for the fine points of the law, bootlegging was a too tempting alternative to the harder ways of making a dollar.

The Bootlegging Life

The owner of the construction company Pressley worked for was a bootlegger on the side. He had two Cadillacs, and soon Pressley was using one of them to deliver illegal booze to thirsty Sherman clients. When he wrecked the car and was fired, he decided to go into the bootlegging business for himself. He was soon turning big, fast profits, at first driving a 1951 Ford and then a larger Buick. Richard Pressley had found a calling.

During the next thirteen years, the law arrested Pressley more than eighty times, convicted him thirty-four times, and collected more than $20,000 in fines for liquor law violations. For the local authorities, bootlegging was a not-so-serious crime, and was on the watch list as long as no violence was involved.

Pressley married a woman who was recently divorced and had two small children. She was a waitress at the Travis Lunch Room, a popular noon time gathering place for downtown working people. The name of the café still stands, big white letters on green tile, over the door of the building a couple of places south of Lamar Street. Pressley would give her a 50 cent tip, a generous gratuity for the times, but, on their dates, he would ask her to return the half dollar.

After the couple married, the family lived at 602 West Cherry. The home sat on nineteen acres that had once been a dairy farm. There were several barns on the property and the Pressleys kept cows, pigs, chickens, and rabbits. The house was surrounded by large trees, and anyone with proper identification could drive through the trees, knock on the back door, and choose from a small selection of illegal booze.

Do you remember Richard Pressley? Share your story.

Click on Leave a Comment at the bottom of this page.

Despite the good money that came in from the bootlegging, times were not always easy for the Pressley family. The couple had three children to join Pressley’s wife’s two, and Pressley’s nephew from Georgia moved to Sherman to live with the family. No one but his wife and his mother-in-law knew Pressley’s dark secret.

The oldest son was a victim of the 1950s polio epidemic. The other two sons and the nephew played football for the Sherman Bearcats, and the coaches permitted Pressley and his wheel-chair bound son to watch the games from the sidelines.

Minnows and Whiskey

The Pressley home place was torn down in 1956 to make way for US 75, and the family moved into a house in west Sherman where Pressley sold minnows from a concrete tank in the front yard and bootleg whiskey from his house. There was plenty to eat, nice home, and money in the bank, but for the children it was solitary confinement. They learned to play, hunt, fish, and fight, like most kids, but there were two strict rules. The children could not spend the night away from home with other children, and the children could not have their friends spend the night at the Pressley home.

Pressley was afraid that the visiting children might stumble upon one of his many stashes of liquor over the false ceiling in the shower, behind wall panels in the garage, or beneath the floor under the family’s big console television set. One hiding place the children would never have discovered was under the back steps, because the steps were so heavy a jack had to be used to uncover the bottles of booze. Bootleggers dealt only in pints and half pints, which were easier to hide than the larger fifths. Most of the whiskey was packaged in eight half pint packages called lugs.

During the many times that lawmen raided the Pressley home, the children were assigned to specific chairs from which they watched television until the police left. The kids were instructed not to take their eyes off the TV because the policemen watched the children’s eyes to see if they might betray the location of Pressley’s stash.

There was another cache of liquor that was always purposely easy to find. When the police raided the Pressley home and found the few bottles of planted whiskey, they would consider the raid a success, look no further, and arrest Pressley. Bootlegging was not a prison offense. An arrested bootlegger usually paid a fine and maybe spent one night in jail. Most raids were a combined effort between city and county lawmen, but even if the city lawmen made the raid alone, they took the bootlegger straight to the county jail on the fifth floor of the courthouse instead of making a stop at the city jail on South Travis.

His daughter said that Pressley did not worry much about the prison escape coming to light and, certainly not about his bootlegging business. Contemporary bootleggers were having tougher times, including getting shot by a jealous husband and committing suicide in a grave yard.

Pressley would get an occasional telephone call from relatives in Georgia, but the children could not stay in the same room with him while he was using the phone. When members of the Thompson family came from Georgia to visit, they used the name Pressley, and the kids never knew the difference.

The fact that Pressley was a bootlegger was common knowledge, edge, and the children were teased and ridiculed. At the public swimming pool, located at the current site of the tennis courts at Houston and US 75, other kids made fun of the Pressley kids, “Your daddy’s a bootlegger! Your daddy’s a bootlegger!”

Pressley built his own 20 x 40 foot swimming pool in the back yard. The son with polio enjoyed the pool so much that Pressley invited any child with a physical affliction to use it. Then he extended an open invitation to patients of the Crippled Children’s Center, a few blocks away, to use the pool for therapy, and the center took him up on his offer.

The March of Dimes was Pressley’s favorite charity. When the polio-stricken son had to be treated in Dallas, the cost was more than Pressley could come up with, and the March of Dimes took up the slack.

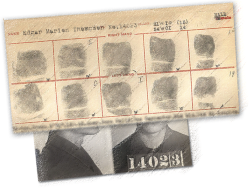

Pressley’s first arrest in Sherman was for drunkenness, and he was finger-printed. When no connection was made with his past after more than a year, he stopped being afraid. The day after he was picked up on the Georgia escape charge, Pressley was quoted in the Sherman Democrat, “I never thought I would be caught. I thought about it a lot, but as the years passed, I felt safer and safer.”

Still, in the back of his mind, he always knew his world would fall apart if his past were exposed. He may have felt “safe,” but he stayed wary. He always carried a small .22 caliber pistol in his pocket, and he once said that if he ever “had to make a run for it, I would knock off the filling station at Willow and Lamar for some quick money and head east.” In those days, Lamar Street was US 82.

Pressley’s fifteen years of freedom came to an end with Sheriff Blanton’s knock on the door, and the secret he had carried so long came out. The next day, the family was called to the courthouse, and, from his jail cell, Pressley told the children the entire story.

The law uncovered Richard Pressley’s past during a raid on his home. One story that circulated suggested that Sheriff Blanton was eager to try out a new fingerprint system and in an unusual procedure in small-time arrests such as Pressley’s, sent the prints to the FBI. The response was quick. The prints belonged to Edgar Marion Thompson, wanted in Georgia for prison escape. The “anonymous tip” that had sent Grayson County lawmen on the raid may have come from his mother-in-law. The two had never gotten along, but why she chose that time to turn him in, no one ever explained.

With the arrest, another problem popped up. The Internal Revenue Service, alerted to Pressley’s background by the publicity following the arrest and disclosures, figured that Pressley owed income tax on his bootlegging profits, and the IRS wanted their money. The Pressleys had to sell all their assets, except their home, to raise the money. A judge in Grayson County bought Pressley’s diamond ring.

Between the time of his arrest and his return to Georgia, Pressley was out of jail on bond, and on the night of June 12, 1960, he played the unwanted part of a hero. He and two other men were fishing on Lake Texoma when they came upon a capsized boat in the dark. All the occupants, two adults and two children, were clinging to the hull. Their name was Dealey, members of the family that owned the Dallas Morning News.

With the exception of Pressley, the rescuers and the rescued were pictured on the front page of the Sherman Democrat the next day. Pressley refused to have his picture taken, and he called a reporter to ask that his name be omitted from any story. He was supposed to be disabled to the point that he could not go fishing, and he was afraid that the story and picture might get back to Georgia authorities. The newspaper did not honor his request, and , since the Democrat was an afternoon paper at the time, the deadline for changes had already passed anyway when he made the call. The story, however, made no mention of Pressley’s criminal record.

As the State of Georgia started the procedure to extradite Pressley, some people in the community began to question whether sending him back to prison was such a good idea. Pressley was five foot ten, 272 pounds, and a diabetic. A Sherman doctor declared him physically disabled and too ill to survive a trip back to Georgia to finish his original sentence and be tried on the escape charge. But, despite the doctor’s diagnosis and a petition with more than a thousand names that had been circulated by his friends, Georgia would not give in completely.

Pressley’s daughter said that the family had belonged to and supported a local Baptist church for thirteen years, but, when the pastor refused to sign the petition that was being circulated asking for leniency in Georgia, they left the church. Then, one day a Methodist minister knocked on their door and voluntarily asked if he could sign the petition. At that point, the Pressleys became Methodists. A Catholic priest also dropped by sometimes for a donation and an occasional mixed drink.

Although Georgia declined to stop the extradition, the petition and Sherman’s support did have an influence on how much more time Pressley would serve. He had done only about a year on the original two to fourteen years armed robbery sentence before he had escaped in 1945, but when Pressley was returned to Georgia late in 1960, he did only eleven months. A prominent Georgia lawyer charged him $1,000 to handle the paperwork for his release.

When he got back to Sherman, he found out that his wife had never stopped bootlegging.

Pressley did not want to be suspected of violating the conditions of his parole, so he rented a house about two blocks from home and raised rabbits for food until he and his wife could find other work.

His wife was a character in her own right. Pressley and some of his bootlegger buddies had a regularly scheduled poker game in Denison. Once, when he was on a losing streak with the family money, she went to the game location, stuck a loaded pistol against his temple, and said, “Honey, we’re going home.” Pressley tossed in his cards in and said, “Boys, I fold.”

Pressley’s bad health caught up with him in December of 1975. After seven heart attacks and two strokes following a lifetime battle with diabetes, he died at age fifty- five. The man with two names also had two death certificates. In Sherman, the death certificate and tombstone read Richard Pressley. But on a Georgia death certificate, the name is Edgar Marion Thompson, the name on a life insurance policy issued in that state. Born Edgar Marion Thompson, he lived as Richard Pressley, and died as both.

Two daughters are the last of the immediate Pressley family. They live in the same house where the family lived in 1960. The swimming pool has been filled in with dirt, but the minnow tank is still in the same place. The only hiding place for illegal liquor is the one under the back steps where they had to use a jack to get to the booze.

Photos provided courtesy of the Pressley family.