This article appeared in the Fall 2008 issue of Texoma Living!.

What you don’t know about Texoma’s toughest lawyer.

If Roger Sanders were an insect, most likely he would be a boll weevil.

Now wait a minute. Before the Sherman lawyer’s friends start raising sand, let us consider the attributes of the little black bug.

Though not universally admired, the boll weevil is a hero to some. The town of Enterprise, Alabama erected a statue to the boll weevil in 1919 to honor the bug for wiping out the cotton crop and forcing the community to expand its economic base. One could argue that the boll weevil was one of the first practitioners of “tough love.”

Boll weevils are resilient little critters that can take the best efforts of their detractors to do them in and keep on keeping on. Boll weevils just don’t know when to give up. Remember the words of the song Southern children learned in grade school:

“Well the farmer took the boll weevil

And he put him on the red hot sand

Well the weevil said this is mighty hot

But I’ll take it like a man

Just lookin’ for a home.

Just lookin’ for a home.”

That fits Roger Sanders pretty well too, for before he came to Sherman thirty or so years ago, he too spent considerable time “just lookin’ for a home.” In atypical fashion for a kid from rural Arkansas, he was a world traveler by the time he graduated from high school—in Bangkok, Thailand.

“My mother worked for the phone company after high school to help her family during the Depression. She was in Mena, Arkansas, when my dad, a dashing Scotch-Irish guy came to town. His mother had died in childbirth, and he’d had a rough time. He was the only male in his family to graduate from either high school or college. I don’t think he was a remarkably talented guy, but there was something in his DNA that made him want to do better and move forward.”

Everette Sanders had studied agriculture and was starting his career as a county agent when he moved to Mena. He and Winifred Craig met, married and started a family. When Roger came along in 1948, at the hospital in Paragould, Arkansas, he joined two sisters, Angela and Brenda, and brother, Craig, to complete the Sanders family.

Top Floor of the World

The life of an agricultural agent was nomadic, from Mena to Mount Ida to Paragould to Newport to Kathmandu. That is Kathmandu, Nepal, as in Mount Everest and Gurkas.

Nepal lies on the southern and eastern slopes of the Himalayas. It is a small country, with Chinese-controlled Tibet to the north and India on the other three sides. Eight of the world’s highest mountains are within its borders. In 1951, to counterbalance Communist China’s aggressive takeover of Tibet, India orchestrated the removal of the ruling Rana party, which had run the country sincethe 1930s, and installed King Tribhuvan. The United States lost no time bringing an American presence to the country.

Everette Sanders had gone to work as an agricultural specialist for the U.S. State Department. Not long after the change in government in Nepal, he and his family joined four other Americans, a doctor, an engineer and two political officers, and all of their families, as part of the first U.S. mission to the top floor of the world.

“I have seen a picture of coolies carrying our Chevy over the Himalayas,” said Sanders, “and we all lived in palaces. They were huge. At least that’s what I remember as a kid. They had butterflies painted on the walls.”

Not only did Sanders live in a palace, he played with a prince and future king, Birenda Bir Bikran. “We had social status. We had automobiles, and I was the only little American boy around his age. We may not have counted for much on the American social map, but because we were Americans, we had connections.” Sanders’s playmate became King Birenda in 1972. The king and most of the members of his family were assassinated at a royal dinner on June 1, 2001.

Amid the splendor of this exotic land, there was a darker side, even for a little boy. “There was communist unrest while we were there, and one of my earliest memories was of being in a little Willys Jeep with canvas side curtains, surrounded by an angry crowd, who were rocking the jeep, shaking their fists and beating on the canvas sides. I remember wondering if we were going to make it out. I was only four, but some of those things stick with you.”

By the time he was six, Sanders had spent one third of his life in Nepal. Then it was back to America and back to Arkansas, back to Mena and back to potato chips. “When you’ve been getting things from the commissary, eating meat patties out of cans and cakes out of cans, it was nice to come home. I remember landing in Hot Springs in a Trans Texas Airways flight and going to a diner for hamburgers and potato chips, Lays Potato Chips. I remember how good it was.” The hamburger sojourn was short lived however, and after a few months in Mena, just enough time to start school, the family headed back to the far side of the world. This time the destination was the Indian city of Shimla.

The British, who made Shimla the summer capital of the British Raj in 1864, had dubbed the city the “Queen of the Hills.” At almost 7,000 feet in elevation and surrounded by forests, the Shimla offered a cool retreat from the scorching summers on India’s plains.

The Brits had left more than pristine city streets; they had left their educational system also, so Sanders was enrolled in the first form of the all boys Bishop Cotton School. “The headmaster’s son, my brother and I were the only white boys in the school. The next year my brother and a sister were shipped off to a missionary school, and I moved to my other sister’s school. It was all girls except for the first four grades. It was an Anglican school, and they hit you if you got the wrong answer.”

An Acorn in a Field of Oaks

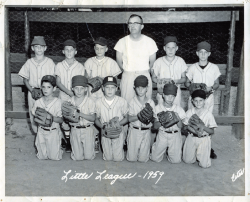

After two years on the sub-continent, the Sanders family came home to Arkansas again. This time the homecoming offered something more than hamburgers and potato chips. It offered baseball. “My father went back to being a county agent, this time in Huntsville,” said Sanders. “That’s where I learned about baseball. I knew nothing about it. I was in the fourth grade, and I lived for recess when we could play ball.”

His love for the game continued when the family moved to Batesville. He played first base and donned the pads and mask of a catcher. The uninitiated may call the gear the “tools of ignorance,” but any ball player who ever flashed a sign to the pitcher knows better. “You’re in on every play. You can try to pick guys off. You can see the whole field. It’s a management position,” Sanders said. “If you’re smart, you can play your way through the position.” He did a short turn at third, but a hot grounder off a rock cost him a front tooth and ended that idea. “We got ten dollars from the insurance company and had to sign a release.”

Adventures in far away lands, an intriguing entry in the background of an older person, was negative baggage for a young boy. “I didn’t belong. Other kids did, but I didn’t. I couldn’t articulate that, but I was concerned that I was always the guy who came into the group last. We were always going to rooted communities. It’s difficult to be an acorn in a field of oaks.”

Experiences that might have scored well with grown-ups did not count so much with kids. “My status as international man of mystery certainly didn’t make me a chick magnet,” Sanders said with a laugh. “I was a Southern kid who talked funny. You spend enough time around a bunch of Brits and you’ll lose your ‘ya’ll.’”

When Sanders was fourteen, the family moved to the big city, North Little Rock. His dad had a better job, and they moved into what should have been a teenage boy’s dream neighborhood. “We had a cheerleader next door and a cheerleader across the street, but I was so socially inept that I was social geek.”

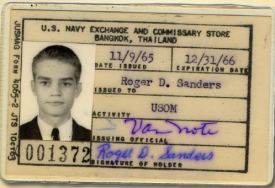

Neither fish nor fowl when it came to social integration with his peers, young Sanders was caught between two very different worlds. That changed before he started his junior year in high school when his father took the family back to the Far East. This time it was Bangkok, Thailand, and this time things were different.

“For the first time, I went into an un-rooted community. There was a good-sized military contingent with military children, who moved around like I did. There were 1,500 students in grades one through twelve in my school. There were 110 in my graduating class. Everybody had gone through the same kinds of things I had, and there was a comfort level. It was like being in the Baskin Robbins line. You may be number six right now, but in a little while you’ll be number one, and somebody else will come in at fifteen.”

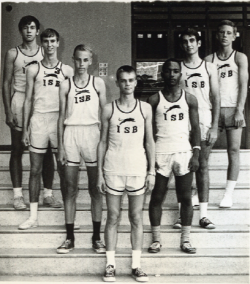

The move to a more congenial environment coincided with a growing confidence. He was coming of age in an environment where he could shine. “I started to run track and won some cross country events. I hadn’t had that kind of experience before. It was a chance to compete. If you could measure up, you could have a chance.”

Roger Sanders, who had bounced from place to place on two sides of the world, had found a place to belong, and he took advantage of it. He was the President of the 1966 Senior Class of the International School of Bangkok and the school’s outstanding athlete. He ran committees, organized fundraisers, and led his classmates on a trip down the River Kwai. No, he did not ride an elephant to the prom.

He did “out” the Bangkok station’s CIA chief, quite by accident of course. “He was new to the station, undercover as a Thai police advisor. When I took his daughter to the senior play, I introduced her to some friends as the daughter of Bangkok’s new CIA guy as a joke. I didn’t really know that it was true until after we left, and she demanded to know how I had found out. Then she swore me to secrecy. For a while, I was scared out of my wits, and I saw enemy agents in every shadow.”

And there was more. “I learned a lot about the humanness of people in power, the sacrifices that they and their families make for their countries. My dad was a great ambassador. He knew about humility. He slept on the floors with the villagers with whom he worked. With him, I saw that public service didn’t have to be glamorous. It could be brick by brick. It could be moment by moment. There was public service by the wives and the children whose husbands and fathers were away from them so much. They sacrificed too. It is a kind of patriotism I don’t think America could survive without.”

He also learned that the diplomats, the civilian representatives and the soldiers were not the only Americans reaching out. “I also got to know another, sort of hidden, set of ambassadors, the Baptist missionaries. Most of them were supremely humble representatives of the Southern Baptist churches. They got by on a limited amount of money, and while I didn’t fully appreciate it at the time, I think they were very effective, quiet ambassadors who reflected a view of America that I was quite comfortable with.”

For Sanders, his two years in Bangkok were “a growing up time,” but growing up also meant stepping out into the larger world. “Somebody told me it was time to apply for college, but I was too busy with sports to be concerned. I took about fifteen minutes, applied to Baylor and Hendrix (a liberal arts college in Conway, Arkansas, associated with the Methodist Church) and decided to go to Baylor.”

Chapter 2

In the fall of 1966, Sanders got ready to trade life in exotic Bangkok for life in decidedly unexotic Waco. But first, he made a detour to Mena to have his tonsils removed. “I couldn’t wait to get out of the hospital and go see my grandmother. She was one of my favorite people in the world. She made great biscuits and cooked squirrel. I was finally getting some sleep after my struggles in the hospital, when she came in, woke me and said she had fixed my favorite meal. It was fried chicken.”

Sore throat, fried chicken, something had to give. “You could have run a rasp down my throat and it would have felt better.” Always the dutiful grandson, Roger choked down a couple of pieces of chicken and then, with tears in his eyes, gave up. He was more than ready to head for Texas.

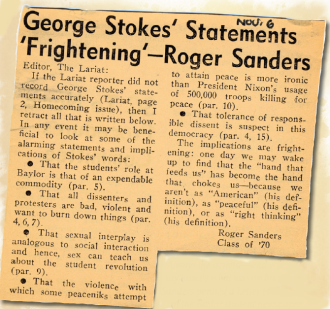

Sanders’s first two years at Baylor, by his own admission, were more political than educational. He was very active in student government and studied just enough to stay in academia’s good graces. He was gearing up to run for student body president, a post he expected to win, when a chance question caused him to rethink what he was doing.

“I was talking with a girl in front of one of the imposing, columned Baylor buildings, and she asked me, ‘Why are you really running for the office?’ I gave her a flip answer, but the question stayed with me. I didn’t have a good answer, and decided I needed to figure some things out.”

Sanders decided that he needed a change of scenery for this introspection and told his friends that he was going to Scotland to attend the University of Edinburgh. Then, when he got around to applying, the Scots politely said, “Thanks, but no thanks.” Sanders wrote back to the university, bared his soul, pled his woeful case, and the school relented. When the term ended at Baylor, he crossed the Atlantic, leaving behind an America roiling in the bitter political struggles of the summer of 1968.

He spent the time before school began taking a pauper’s tour of Europe and then making a visit to his family. They were back in India, in New Delhi. It was a homecoming, but only for a short while. It was time to step away from hearth and home. “I lived on top of an apartment building that was covered with monkeys. I spent the rest of the summer, reading, listening to music and hanging out with the monkeys.” He also made the time to learn something about Hinduism and read about Gandhi.

Sanders’s time at university was another expansion of his world. The old city of Edinburgh, so sophisticated, so European, where the skirl of pipes broke the cool morning air and the buildings carried centuries of history on their stones, enthralled him. And he learned to better appreciate the material advantages he had. “My roommate was from southern England. He came to college with only two shirts and a pair of pants, and I used to think I didn’t have anything.”

He discovered Simon and Garfunkel and learned how to get drunk. He traveled around Scotland and went on a British Student Union trip to Poland and the Soviet Union. In Moscow, the attractive blond Russian travel guide assigned to his group pulled Sanders into an alley one night after the others had gone back to the hotel. She wanted out of Russia. “Her plan was for us to marry, saying we could divorce later in the States. My naiveté was melting away.”

A friend from Arkansas was at Oxford. Sanders went down for a visit one weekend and there met his friend’s roommate, who was also from the Land of Opportunity. “He was curly headed and round cheeked and talked incessantly,” Sanders recalled. “He was a nice fellow, but he thought he knew everything. He was just full of himself. As I was leaving, he asked me, ‘What are you going to do when you go back to the States?’ Jesting I said, ‘I’m going to be governor of Arkansas.’

“It was like I had hit him in the face. He said, ‘You can’t do that. I’m gonna be governor of Arkansas.’ I said, ‘OK, you take Arkansas, and I’ll take Texas,’ and I said goodbye to Bill Clinton.” He said goodbye to England and Scotland too, and headed back to Baylor to begin law school on a scholarship. (He was in a three and three program, three years as an undergrad then three years in law school, after which he would graduate with both a B.A. and a J.D.) At least that was the plan.

“Baylor denied my scholarship to law school because I had stood with some professors at a prayer vigil about Vietnam. The dean said I would have to prove myself.” With no scholarship in hand, Sanders prepared to go back to undergraduate school. At least that was the new plan.

That same year, 1969, the Selective Service System held the first draft lottery. Gone were the easy deferments, and Sanders’ slow number—it was 94—was a guaranteed ticket to the U.S. Army and probably Vietnam. Rather than wait for the other combat boot to drop, Sanders joined the Texas National Guard and left for six months of basic training at Fort Polk, Louisiana, and jump school at Fort Benning, Georgia.

A Call of Conscience

Sanders’s six months with Uncle Sam were not particularly notable save for one incident, which he says affected him greatly. “I think back on that episode as having a great impact on my life.”

The training cycle before the one Sanders was in had seen an ugly racial incident between black and white soldiers, and the atmosphere was still loaded. The noncoms tried to keep a tight rein on things, but they were not always successful. In his platoon were a couple of white soldiers, Sanders described them as “two frat rats,” who constantly pushed the black soldiers with slights and slurs. Sanders’s inclinations put him on the side of the targets.

“About two o’clock one morning, a black guy from Houston woke me up for fire guard duty and told me to make myself scarce,” said Sanders. “He showed me a pistol and said ‘I’m gonna go kill those two guys.’ I was putting on my boots and trying to think how to stop this from happening. I had some malt liquor, and—the short version—I got him drunk and got him out of there. It may have been my first opportunity to do something to make a difference.”

Until it happens, no man really knows how he will react to a chilling choice to stand up or step down, but choosing the one over the other can become an action of habit as much as of moral certitude. It is a habit that Roger Sanders long ago acquired. Perhaps that long night in that dark barracks is where it began, but more likely, it was an ethic inculcated from childhood, drawn from examples he saw around him.

“My parents were always very respectful of other races and other ethnicities. I never heard them use the kind of language common in our part of the country toward blacks and Hispanics. They were unusual for people of that day and time and that education. Maybe that’s why I sort of always gravitated toward the underdog. I’ve often wondered. Perhaps it’s the indelible call of conscience. You can do nothing else.”

During his stint in Basic Training, letters from his Baylor girlfriend Cynthia Arden Smith helped keep up his moral. “She was from Plainview, had been a beauty queen and had an opera quality voice, and was really smart. Friends had set us up so we were obligated. Our first date was so bad. I took her to the Cuckoo Burger, and with typical Sanders planning, I only had enough money to buy her a meal, so I had salt and pepper.”

Duty done, the pair went their separate ways, but then something, perhaps some mystic cosmic power intervened. “While I was in Edinburgh, a pseudopsychic friend told her that someone named Roger was going to be important in her life. Later on, he told her she would marry someone who had lived overseas half his life. She and her girlfriends figured that out, and when I came back from Edinburgh, she stopped me in the hallway of the student union building, told me the story and said, ‘We need to date.’ That’s the kind of woman she was. She knew what she wanted.” Cindi and Roger were married in June 1971, just after he started law school.

Cindi got a master’s degree in audiology and speech therapy, and that got the young couple though three years of Baylor Law. With a Texas Bar certificate in hand, Sanders pondered what to do and how to do it. He still had political aspirations, but Texas was a big and a bit daunting place, so the couple headed for New Mexico. “It only had a million or so people. That was easier than Texas, and Bill Clinton had claimed Arkansas, so I went out there and interviewed for a job with the National Labor Relations Board.” Despite the apparent handicap of no experience, he got the job. “I’d never even had a class in labor law,” he said, “but I interviewed well.”

Sanders’s enchantment with the State of Enchantment didn’t last very long. The problem was not so much with New Mexico or Albuquerque, as with the job and the pettifogging, backbiting, bureaucratic one-upmanship and a boss who would not let Sanders near a courtroom. After six months, he quit.

Before the New Mexico sojourn, Sanders had interviewed with a Sherman law firm, so he knew at least a little about the town. He and Cindi had already decided they wanted to live in a community about Sherman’s size, and they had considered Liberty, Tyler, Longview and a few others.

Why small? Why not the buzz of the cities, Dallas or Houston? “Both of us liked the qualities we sensed in a small town, so that’s where we wanted to go, but we didn’t want to go where our relatives were, so that ruled out Temple (he had an uncle there) and Plainview. We were looking for something that felt familiar.

“I needed some place to finish growing up. I had not been socialized. I was a country boy who had been to sophisticated places. My wife made me, good or bad, but I was not a Houston, ‘let’s go hang out with the swinging crowd’ kind of person. That’s just not who I was. She wasn’t either. For all her sophistication, and she had a lot of it, she was a small town girl. A small town fit us, and we thought it was a place our kids could be brought up safe and be educated in a public school system. That was important too, because that’s what you do in a democracy.” Sherman had what Roger and Cindi wanted, and it had something else, a job.

Roger and Cindi moved to Sherman in 1974. Sanders joined the three-man firm (he made it four) of Kennedy and Minshew making half of what he had earned working for the government, but in much more congenial surroundings. “I worked directly with Jack Kennedy doing trial work. He was the best,” Sanders said. “Jack [Kennedy] and Bob [Minshew] never restricted me on the kinds of cases I could take, so I learned about pretty much everything. I had over 200 case files.”

Fourteen months after starting with the firm, Sanders moved down the street to join Don Jarvis and Ray Grisham. He needed a little more room to take on things he thought were important and make his mark.

Sometime early in his legal career, indeed, well before he hung up his shingle perhaps, Roger Sanders must have read the comment about newspapers by Finley Peter Dunne, “The job of a newspaper is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable,” and decided it applied to lawyers as well.

In the early days, it was not a very lucrative choice, at least not in financial terms, but Cindi worked for the schools and later a hospital, and they made do. “You can’t have a BMW car payment and take those kind of cases, so I had a Plymouth Valiant with no air conditioning. If you make a low-cost lifestyle choice, you have more options.” Things got better.

Sanders’s thirty-five years at the bar have been marked by cases and causes large and small, some won, some lost, but most of the time it seems as if he has fulfilled Finley Peter Dunne’s directive pretty well. He has made a habit of taking the cases no one else wanted.

Because of that willingness to step up, Sanders has become an amiable irritant to some of the more staid segments of the establishment. They respect him, but they also are a little bit afraid of him and do not altogether appreciate his combative representation of the often unpopular. Consequently, Sanders has remained on the edge of the legal and social structure in the community. No longer an acorn in a field of oaks, he is perhaps a hickory, not so much out of place as simply different.

Despite whatever disapprobation may be directed his way by the establishment, he is a champion to the people he has helped. After a ten-year, difficult, costly, essentially unpaid and ultimately successful battle to keep a landfill out of the city of Bells, the citizens of the town named a park after Sanders. He had not sought the case. “I had turned it down, but I guess that perhaps unconsciously I put myself in the swirl of events, and it came back.

“I had never intended that kind of investment, but one thing led to another. Besides, the beans, cornbread and pie suppers were great, and the Bells folks were solid and good to work with, especially in the darkest times.

“Once, when the council members had been sent a formal letter threatening them with an $800,000 legal claim by [the opposition] there was this long silence around the old Bells city hall. Finally, one of the councilors broke the silence. ‘How much do they want from me?’ Eight hundred thousand dollars, I told him.

“’Well for a minute there I was scared. I thought you said $800. I got that and that would have worried me; but $800,000? I don’t have that. So let’s fight.’ That was their attitude, over and over again.”

Long ago, Roger Sanders chose the direction his life in the law would take, and he has not strayed from the path. The road has gotten smoother, easier perhaps, certainly more economically rewarding, and it has been fun. He has come this far, and is not likely to change his ways. As Darrell Royal remarked when asked if his Longhorns would change their football strategy for a big game, “No, I reckon we’ll dance with them that brung us.”

In 1992, Sanders’s long-submerged political aspirations surfaced, and he decided to take on Congressman Ralph Hall in the Democratic Primary. “I think I was kind of bored doing what I was doing,” said Sanders. “I think, like other times in my life, I just needed to get out of Dodge, nothing high minded, nothing particularly noble.”

Despite the quixotic nature of taking on a long-time, well-financed and popular politician, Sanders said he really thought he could win. Toward the end of the campaign, he was ahead in the polls in several counties in the district, and then he ran out of money. “Ralph Hall is a smart guy, and nobody dislikes him. The last couple of weeks the airways were covered with his TV. I didn’t have it. That doesn’t mean to say I would have won if I’d had it, but there had been some momentum, and then it just ebbed away. He handed me my head. The mechanics of politics were far more powerful than the idealism I brought to the contest.”

For years, Roger Sanders had worked long, hard hours and invested much of his ardor, interest and attention to the ideas and causes that mattered to him. It is a common enough phenomenon with men driven by concerns both noble and base. So is a common and unfortunate corollary that what the cause gains, the family often loses. For Sanders, the intensity of the political campaign exacerbated his inability to recognize what was happening to his wife.

Chapter 4 – The Hardest Decision

There is no gentle way to recount what happened to Cindi Sanders. Her husband does not attempt to. “Perhaps it will help someone else,” he suggested. “Cindi suffered from clinical depression, and in the course of her treatment she became addicted to prescription drugs. The physician just couldn’t see past his book learning when I told him she was sinking. This was not working.”

After a variety of treatments, Sanders sought help for his wife at the Mayo Clinic in 1993, but those efforts failed also. The doctors there suggested, insisted is more like it, that Roger file for divorce to reinforce the consequences for Cindi if she did not fully cooperate with the treatment. “So, after talking to my pastor and close friends, I filed for divorce. It was the hardest decision of my entire life.”

The addiction was all consuming. It overwhelmed her capacity to resist and negated the efforts of her family, friends and the medical community to help her. No one wanted the divorce. There was counseling and efforts at conciliation, but there was no answer. There was no solution. Things only grew worse until the divorce action ceased to be a tactic, and became a strategic necessity for the protection of the couple’s three young daughters. Roger Sanders was a man long used to stepping up, reaching out and leading the fight, but this battle was beyond him, beyond anyone.

“I don’t attribute guilt to anybody,” he said, “but I don’t think our society is equipped to deal with the power of addiction. It is frequently described as ‘cunning, powerful and baffling,’ personal characteristics. The terms give some sense of how the personality is absorbed by the power of the addiction.

“Cindi was a lovely person. That is not to say she was without fl aws, saintly, but she was a good person. She never let me pass anyone without offering to help. She had that kind of heart. That essential goodness is reflected in our three daughters. She was my best friend for twenty-three years. I still don’t understand why this had to be.”

Perhaps that is the most difficult thing. We seek answers, reasons for things, which are in fact beyond our control, as if by knowing why, we can somehow reach back in time and alter the outcome. We take no solace in the arbitrary nature of life.

His wife’s illness made relationships with the family’s friends achingly awkward. “You have this relationship and suddenly you don’t. People quit talking to me; quit associating with me. They did it because they didn’t know what to do. There was such heartbreak.

“Who counsels the friends? How do they express heartbreak for Cindi, who was well known and well regarded? How do you express that? We run into all the awkwardness of things that are just below the surface, that are clearly true in the poetry of life, but are clearly denied in order to protect our emotional well-being. So the awkwardness is embraced by silence and denial.”

After the divorce, Cynthia Arden Sanders lived under the care of a sister in Fort Worth. She died about a year later. Rather than the private, graveside service in Plainview planned by her family, Roger brought her home to Sherman. He asked six judges to serve as pallbearers. “I wanted her honored for her life. It wasn’t fair to her to do any less.”

Lawyers live a life of words. They build their professional lives around the use of the language to clarify, to explain, to cajole, to persuade, to inspire. Roger Sanders’s experience of being with out the words needed to express a too painful grief led him to develop a collection of grief cards with his daughter, Rebecca. One of them reads, “I don’t know what to say… I don’t know how to say it … I just know I have to try …”

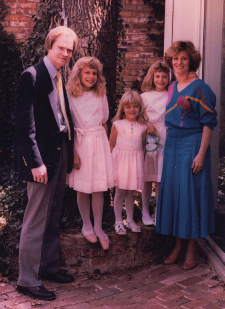

Roger Sanders seems a man at ease with himself. Age helps develop that along with the realization that so many things that seemed so important in one’s youth, turned out to be not so important after all. His three daughters, Arden, Rebecca, and Alexis, all grown, all notably accomplished, are making their own ways in the world. Arden, the oldest, lives in Pottsboro and has two children, Bailey who is three and Trey Allen who came along in February. Rebecca is working on a doctorate in Berkeley, California, and Alexis, a graduate of University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business is an investment banker and business consultant in Portland, Oregon.

Long active in the Presbyterian Church, Sanders became a lay pastor, and he regularly leads a Bible study class. He also teaches a life skills class at the Four Rivers Mission, a nondenominational outreach program in Sherman for people with addictions. He teaches a regular business law course at Austin College. (“I’m not sure the students would describe it as regular anything,” he said.)

He even developed and got a copyright on a board game entitled, “The Pratfalls of the Primetime Preacher.” “My kids loved the game, but I found out it would cost about $40,000 to self-publish it.” It is not available in fine or not so fine stores anywhere.

As for his legal career, “I’m pretty good at organizing things, managing cases. I’d like to find a way to help the disadvantaged by simplifying and explaining what’s happened to them, something along the lines of a legal diagnostician, to help even the odds for the little guy in court.”

In the non-legal arena, Sanders has several projects that are calling for his attention. “I’m working on a website calling for corporate respect for the essential standards of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This American initiative, adopted by the U.N. in 1948, promotes a certain minimal level of humane treatment for everyone everywhere.”

In April, Sanders went to Stockholm to study at a school for nonviolent communication. “I would like to be involved in peace making,” he said. He has made other peace-related trips to Iraq, Colombia, and Poland.

Whether or not his interest in peace making and conciliation means Roger Sanders will be more open to compromise with his opposite numbers in court is unsettled. He might be, but don’t count on it. It’s just not a boll weevil thing.

Hi Roger, I enjoyed reading about you. I am also a Sanders living in Orange Beach Alabama. Take Care & Best Regards, B. Sanders