This article appeared in the January-February 2010 issue of Texoma Living! Magazine.

By Willie Jacobs

The bootlegger flinched twice, once when I jacked a shell into the chamber of the sawed-off 12-gauge and again when I jammed the muzzle against his left ear. To me, the backward-forward action of the shotgun was a smooth schnick-schnick. To him, it must have sounded like thunder.

The smell in my nostrils was fear and oil fumes. He was scared. I was scared. The old Ford was puffing blue smoke through the floorboard. I had the side of the gun pressed against my cheek, and the moisture on my face and the shotgun was my sweat.

Even in the dimness of the dome light, I could see beads of perspiration on the face of the bootlegger behind the wheel. His chin was bleeding from landing face down in the gravel road when he had fallen in his escape attempt. His ear was oozing blood, but the wound was not intentional. I was neither that tough nor that mean. He had tried to get out of the car at the same second I decided to get closer. The collision of muzzle and head almost took off his ear lobe, and he never moved again. His hands were frozen on the steering wheel. His eyes moved neither right nor left. “I’ll be good! Don’t shoot me!” he said.

I heard a “pop, pop, pop” and saw three quick muzzle flashes a few yards away…

I heard a “pop, pop, pop” and saw three quick muzzle flashes a few yards away, as the detective who had given me a ride earlier that evening fired his snub-nosed .38 detective special in the direction of a fleeing Lincoln. The second bootlegger was getting away.

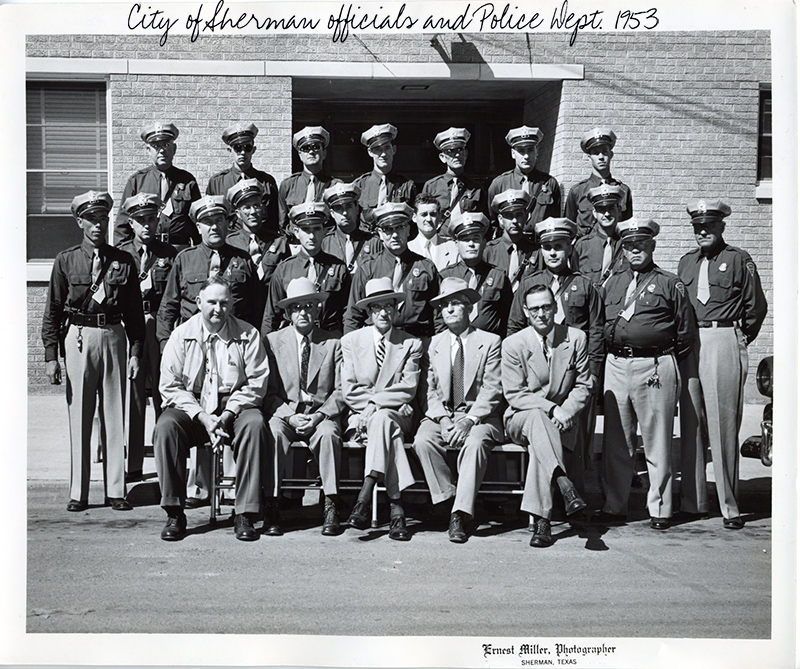

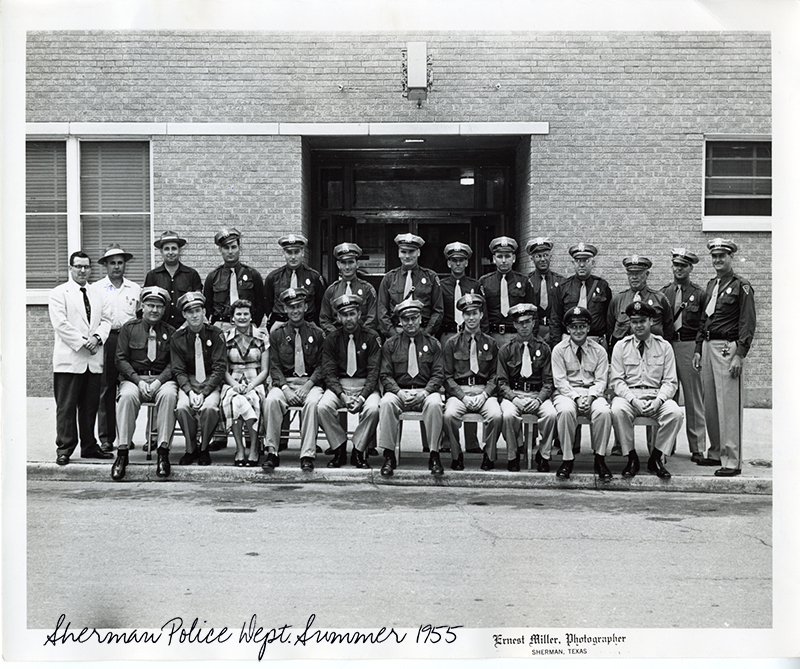

The year was 1956. Bootlegging was the number one crime in Grayson County and a way of life in Sherman and Denison. Thirsty drinkers were willing pay for their liquor, and a bootlegger could double his money hauling hooch up US 75, the two-lane ribbon of concrete that connected Sherman to Dallas.

I was a twenty-one-year-old rookie police reporter when I hitched a ride with Johnny Garmon, a detective with the Sherman Police Department and a friend of mind. It was a little after midnight on a Saturday when he picked me up at the front door of the Sherman Democrat on the southeast corner of the courthouse square.

We went looking for a pair of chicken fried steaks out on the Denison highway and settled for a pair of bootleggers and some gunshots on Gallagher Road. Nothing like that had ever been mentioned in Journalism 101 at North Texas State.

We were in an unmarked police car. A man driving a near-ancient, smoking, oil-burning old Ford passed us on Walnut Street, which was one way and ran north. The car’s front end was high, and the rear bumper was nearly dragging the concrete.

Garmon recognized the man as a local bootlegger. “That guy’s settin’ low with a load of whiskey,” he said, as he stepped on the gas. When the old Ford turned onto Loy Lake Road, Garmon turned his headlights off and followed several hundred yards back.

When the Ford turned east onto Gallagher, Garmon stopped in the dark. We were south of the spot where Loy Lake Road crosses US 82 today. There were no houses and no trees in the area in 1956, nothing but Johnson grass and a few oil wells. The last Loy Lake Road address listed in the 1956 Sherman city directory is 2626, today’s location of First Texoma National Bank.

The detective pulled out a pair of binoculars and peered into the night. There was nothing to block his view when the Ford met another car driving west. They drove past each other, stopped, and then backed up until their rear bumpers were almost touching. The two cars stopped again where Northridge meets Gallagher today.

Two men, one black and one white, were moving cases of whiskey from the old Ford into the huge trunk of a new Lincoln.

Garmon flipped on his lights and drove slowly past the two cars. Two men, one black and one white, were moving cases of whiskey from the old Ford into the huge trunk of a new Lincoln. Both engines were running. The men didn’t even look up from their work as we rolled by. When we got to US 75 (now Texoma Parkway), Garmon turned around and turned his lights off again.

Then it got serious. Garmon reached under the front seat and handed me a sawed-off 12-gauge pump. “You are duly deputized. It’s loaded. You’ll have to put one in the chamber. You take the black guy, and I’ll take the white guy.” Then, almost as an afterthought, he added, “You do know how to put one in the chamber, don’t you?” I nodded, too scared to speak. My dad had first put a shotgun in my hands when I was about ten years old.

The bootleggers were so busy with their chores that they never noticed that our car had rolled quietly up on the scene. Then Garmon stepped out, pistol drawn, and said, “Hands up, and stand where you are.”

“Don’t move.” That’s what I said because that’s what they said in the movies in situations like that.

The black man made the first break, but I was standing on the driver’s side of his car. He stumbled, swore as he fell face first in the gravel, scrambled up and got into the car. He didn’t get the door closed before I said, “Don’t move.” That’s what I said because that’s what they said in the movies in situations like that.

The Lincoln was between Garmon and the white man, and he didn’t even close his door as he dove into the car and gunned it, sending a shower of gravel over both of us, as he left the road and circled south and back east through the Johnson grass, headed for Denison.

Garmon moved into the waist-deep grass, stood in one place, and pivoted as he fired his snub-nosed .38 special three times. The Lincoln never slowed, as it careened out of the field and bounced through a ditch back onto the gravel road. The trunk lid, which the bootlegger did not have time to close, was flapping, but no whiskey was lost.

The detective jerked the bleeding prisoner out of the old Ford and into our back seat, and we gave chase.

The detective jerked the bleeding prisoner out of the old Ford and into our back seat, and we gave chase. The police car was no match for the bootlegger’s ride. It choked down and cut out at about eighty, and the second car got away clean. Well, not exactly clean. Tuesday morning, Fort Worth police found the Lincoln on a used car lot. It had three bullet holes in the trunk and long stalks of Johnson grass in the frame.

I didn’t sleep much that night after I got back to my garage apartment on Ross Street. Was what I had done legal? Garmon had said it was legal. Had either of the two men been armed? Would a black man with a big scab on his left ear come looking for me when he got out of jail?

When my dad was teaching me gun safety, he had said, “You don’t get to be dead but once!” I knew what I had done that night was dangerous, but it took a while for the events of the evening to sink in. It was a night I would never forget, and friend Johnny Garmon helped etch the story in my mind and in his when he laughed and told the story in my presence, probably a dozen times, to police friends or anybody who would listen.

Burglaries took over the top crime spot in Grayson County in 1960, after a liquor election in which Denison voters opted to go wet and buy booze at home.

Burglaries took over the top crime spot in Grayson County in 1960, after a liquor election in which Denison voters opted to go wet and buy booze at home. Before the election, proponents declared that any person ever convicted of the illegal transportation or sale of alcoholic beverages would not be allowed to obtain a liquor sales license. The man in the Lincoln was one of the first to be approved, and he prospered in the liquor business for many years.

Peddling whiskey was not a prison offense. There were just fines, maybe a night in jail. A bootlegger behind bars told me, “Fines is a business expense. You pay income tax. I pay fines. I’ll be out and selling again tomorrow morning.”

B. F. Wade, Sherman resident in his sixtieth year of law enforcement, most of it with the Texas Highway Patrol, chased his share of bootleggers. Wade said that most arrests came from informants’ tips, and the best informants were Dallas liquor stores. “The stores always had a man watching the competition,” he recalled. “If a bootlegger bought from one store, the other store would tip off the highway patrol.”

There was also a kickback system, which Wade explained. If the bootlegger paid 10 percent of his projected gross up front to the liquor store where he was buying his booze, he had a guarantee that the store would not call the highway patrol. It was the old protection racket, “pay me and I won’t tell.”

For a while during the mid-fifties, Wade was the only highway patrolman in Grayson County, and the bootleggers knew it. They would call his home at night. If he answered, they knew he was not on patrol, and they would make a run. If he did not answer, the bootlegger usually waited until a safer time.

In the movies, the bootleggers always drove souped-up, cars and the law had a hard time catching them. Not in Grayson County, Wade said. “They drove stock cars, and they were not any faster than our patrol cars. Plus, we had the experience of knowing how to drive fast better than they did, and we knew our roads better.” In 1956, he drove a new Ford.

He said that he never shot at a bootlegger, and, as far as he knew, no bootlegger ever shot at him. But did some of them have weapons? “They were outlaws,” he said. “I’m sure they did.”

It was a long drive to a legal drink back then. Even Oklahoma was dry, well, sort of. Across the Red River, they sold a legal low-alcohol beverage called “near beer.” Signs in stores explained it. “No beer near here. Near beer sold here.” That was good enough for teenagers looking for a buzz, but not near good enough for serious drinkers.

J. D. Pickens, retired Sherman chief of police who still lives in the city, recalled two Durant brothers, regular Dallas customers, who owned identical Oldsmobiles. When the police chased them, one Olds served as a decoy, while the other one hauled the booze. They had no qualms about swapping license plates between the two cars. Wade remembered two identical white Cadillacs that played the same game.

Bootlegging took more law enforcement time than most crimes, and it was a game of hide and seek for the law and the lawless. Most bootleggers hid their stash in their homes, and they hid it well.

One man, who was a carpenter by trade, built an elaborate system with a secret door. When a heavy, stiff wire with a crook on the end was inserted into a hole in the bottom of a kitchen cabinet a secret panel would open and display the entire inventory of illicit booze. Years later, long after his bootlegging days had ended, the owner of the cabinet was gunned down inside a shower stall where he was working.

In another case, the policemen had just about given up in a search in a particular house, when J. D. Pickens noticed that the screws inside a bathroom medicine cabinet were not tight. He loosened the screws even more, and, when he pulled the cabinet out of the wall, a pint of whiskey popped up. The bootlegger had a homemade vending machine between the walls with a spring under the bottles. When one pint was taken, another came to the top.

One enterprising bootlegger also sold minnows from a concrete tank between his house and the street. A hose on the ground near the tank rang a bell when a car passed over it. If the bell rang twice, the front wheels and then the back wheels rolling over the alarm, the man went out and sold a bucket of minnows. Drivers in the know drove over the alarm once and then backed over it again, causing multiple rings of the bell. They got a different service.

When the sheriff’s office busted this fishy business, Sheriff Woody Blanton sent the minnow man’s fingerprints to the FBI in Washington. It was not routine for minor offenses, but Blanton’s office had just installed a sophisticated fingerprint system, and the sheriff wanted to try it out.

The response from the bureau was quick. The minnow salesman was wanted in Georgia, where he had been part of a mass escape from a chain gang and a guard had been killed. Although he did not take part in the killing, he was still a fugitive. Shortly after his escape, he had moved to Sherman and changed his name.

Extradition was stymied when a doctor testified that the man had a disability that would make him physically unable to go back to Georgia to serve out his original sentence or even face trial on the escape charge. When old-time lawmen tell the story today, some say he went back to Georgia, but was released after serving only a part of his prison term. Others say he never left Sherman before he died.

That minnow tank is still in the same place that it was in 1956, and some of the lawmen of that day are still swapping stories about chasing bootleggers, and some of the old bootleggers are still swapping stories about being chased. But, bootlegging? Well, bootlegging got killed at the ballot box almost fifty years ago.

History of the Bootlegger

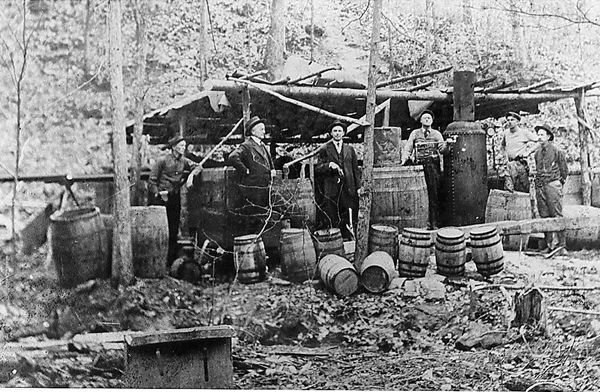

Did you ever wonder about the term “bootlegger”? The term reaches back to at least 1889 as a reference to smugglers who carried illicit bottles of whiskey down the tops of their boots. It’s a colorful use of the language, not surprising as criminal cant often makes imaginative use of words to obfuscate the speaker’s true meaning. The illicit making, transporting and selling of whiskey if fill with such argot. Make it without a license and it’s “moonshine.”

Logic suggests that the term comes working at night under the moon to hide the activity, but in parts of England, the term also meant “nothing of importance,” and that meaning may have been used by smugglers to describe their goods. If the man with a “thirst” couldn’t afford a jug, he could get a single drink at a “shot house.”

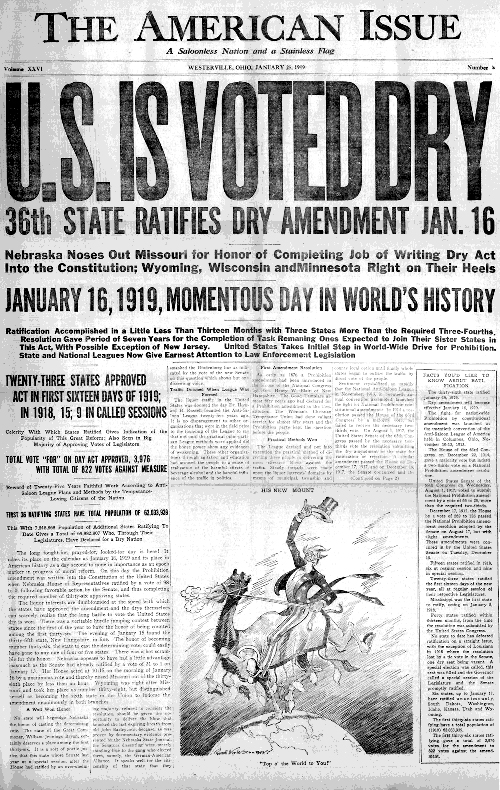

With the ratification of the 18th Amendment in 1919, and the passing of the Volstead Act to enforce it, illegal bars became “speakeasies” as patrons would be warned by the bartender not to call attention to what was going on, to “speak easy.”

The tipplers downed “bathtub gin,” made by “alky cookers” or tasted “the real McCoy” smuggled past the Coast Guard by “rum runners.” Down South, a illegal bar operating behind a legitimate business front was called a “blind tiger” or “blind pig” sold “white lightning,” “hooch,” or just “shine.”

With the repeal of the 18th Amendment by the ratification of the 21st Amendment on December 5, 1933, control of alcoholic beverages— except for federal tax purposes— became a state matter once again, and the bootlegger became an agent of convenience rather than need. That’s what made the business a profitable one in dry Grayson County in the 1950s.

Editors note: Willie Jacobs, long-time Sherman resident, one-time rock-a-billy singer, long-time voice of Austin College football, and currently an insurance executive, started his career in Sherman in the mid 1950s as a reporter for the Sherman Democrat. At the request of Texoma Living! Jacobs recounted those days.